- Home >

- Royal chateau of Blois >

- Collection >

- Not to be missed

Not to be missed

More than 1000 objects are exhibited in the permanent rooms of the Chateau, particularly in the Fine Arts Museum and the Royal Apartments. The other items in the collections have been conserved in reserve, and are occasionally either presented in temporary exhibits or deposited in other French museums.

You are now about to discover some of the premier pieces found in our collections.

Portrait of Antonietta Gonsalvus, by Lavinia Fontana (c. 1595)

The girl with the hairy face portrayed by Fontana suffered from a genetic disease called hypertrichosis, also known as the "werewolf syndrome". Just like her father, Pedro Gonsalvus, she presented an abnormal pilosity.

The girl with the hairy face portrayed by Fontana suffered from a genetic disease called hypertrichosis, also known as the "werewolf syndrome". Just like her father, Pedro Gonsalvus, she presented an abnormal pilosity.

At a time when princes were prone to create « curiosity cabinets », fascination for this type of phenomenon reflected a more general appetite for the freakish and the extraordinary; that is why Antonietta was invited to European courts.

The story of the Gonsalvus family is representative of the literary tradition of the « wild man », and it returned to prominence in the 18th century with the celebrated tale: « Beauty and the Beast ». Moreover, a depiction of Antonietta Gonsalvus's father served as a model for the mask of Jean Marais in the 1946 film of this title by Jean Cocteau.

Oil on canvas (Inv. 997.1.1), acquisition by the town of Blois. This painting is displayed in the Queen’s Chamber, in the François 1 wing.

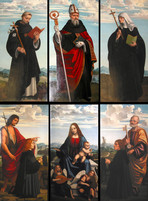

Six-panel polyptych, by Marco of Oggiono (c. 1500-1510)

Representing on top from left to right: Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, Saint Augustine, Saint Monique; at the bottom: Saint John the Baptist, The Virgin and the Infant, Saint Peter.

Representing on top from left to right: Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, Saint Augustine, Saint Monique; at the bottom: Saint John the Baptist, The Virgin and the Infant, Saint Peter.

This monumental altarpiece, which originally measured 12 square meters, initially adorned the altar of a church, most likely in the vicinity of Milan. It bears the signature of the painter Marco d'Oggiono, the main student of Leonardo da Vinci. The Master's influence is pronounced, particularly in the face of the Virgin, which is reminiscent of Leonardo's painting of the Virgin of the Rocks, which has been conserved in the Louvre.

Oil on wood, deposit of the Louvre museum, Inv. MNR 272, 270, 271, 264, 269, 263). This work is displayed in Room 1 of the Fine Arts Museum.

The Abduction of Europe, by Jean Cousin (c. 1570)

Under the spell of Princess Europe, Jupiter disguised himself as a white bull so as to get close to her and spirit her away to Crete. This amorous myth met with splendid success in Renaissance painting. The light-hearted theme and gracious style characterize the refined art that took hold in 16th-century France under the influence of the royal court. This painting once decorated the fireplace of a private mansion in Blois that, unfortunately, was bombarded in 1940.

Under the spell of Princess Europe, Jupiter disguised himself as a white bull so as to get close to her and spirit her away to Crete. This amorous myth met with splendid success in Renaissance painting. The light-hearted theme and gracious style characterize the refined art that took hold in 16th-century France under the influence of the royal court. This painting once decorated the fireplace of a private mansion in Blois that, unfortunately, was bombarded in 1940.

Oil on wood - (Inv. 860.1.11). This painting is displayed in the Valois Room, in the François 1 wing.

Allegory of Good Government, from the workshop of Pierre Paul Rubens (c. 1625)

This imposing painting is an allegory, that is to say a personage embodying a concept. In this case, the woman represents Good Government. The scepter she holds in her hand is a manifestation of her power, and the rudder at her feet allows her to effectively steer her people. She tramples the weapons symbolizing war. Her peaceable reign delivers Prosperity (cornucopia: the horn of plenty) and Justice (the scale). This picture was no doubt brought into being by artists close to Rubens; the decor is that of the Luxembourg Palace, residence of Marie de Medicis and long-time workplace of the Flemish Baroque master.

This imposing painting is an allegory, that is to say a personage embodying a concept. In this case, the woman represents Good Government. The scepter she holds in her hand is a manifestation of her power, and the rudder at her feet allows her to effectively steer her people. She tramples the weapons symbolizing war. Her peaceable reign delivers Prosperity (cornucopia: the horn of plenty) and Justice (the scale). This picture was no doubt brought into being by artists close to Rubens; the decor is that of the Luxembourg Palace, residence of Marie de Medicis and long-time workplace of the Flemish Baroque master.

Oil on canvas (Inv. D.56.1.1, deposit of the Louvre museum). This painting is displayed in Room 2 of the Fine Arts Museum.

Psyche declining divine honors, by François Boucher (c. 1740)

While the extraordinary beauty of Psyche led enraptured men to adore her as a goddess supplanting Venus, in this representation she can be seen refusing the gifts proffered by her adorers. Unfortunately, it is too late: Jealous and enraged, Venus appears and orders Cupid to punish her, but he falls in love with Psyche and arranges for her to be taken to his palace...

While the extraordinary beauty of Psyche led enraptured men to adore her as a goddess supplanting Venus, in this representation she can be seen refusing the gifts proffered by her adorers. Unfortunately, it is too late: Jealous and enraged, Venus appears and orders Cupid to punish her, but he falls in love with Psyche and arranges for her to be taken to his palace...

The tumultuous loves and the stormy weather surrounding Psyche and Cupid were a hot topic in the 18th century. They corresponded to a shared predilection for seductive art, which aimed above all to please. A certain lightness of being shows its colors in this rough sketch, which constitutes preparatory work by an artist about to produce a tapestry.

Oil on paper marouflaged to canvas (Inv. 882.4.2), bequest of M. Rosat between 1872 and 1882. This work is displayed in Room 4 of the Fine Arts Museum.

Francis I hunting, by Theodore Gechter (1843)

This decorative bronze object is a representation of François I hunting wild boar. The sculptor portrays a great Renaissance king partaking in an activity he treasured, and which attested to his courage. In the 19th century it was highly fashionable to celebrate bygone centuries and illustrious figures.

This decorative bronze object is a representation of François I hunting wild boar. The sculptor portrays a great Renaissance king partaking in an activity he treasured, and which attested to his courage. In the 19th century it was highly fashionable to celebrate bygone centuries and illustrious figures.

(Inv. 2001.7.1, acquisition by the town of Blois).This sculpture is displayed in the King’s Room, in the François 1 wing.

Valentine of Milan mourning her husband, by Marie-Philippe Coupin de la Couperie (1822)

It was to no avail that Valentine Visconti, whose husband Louis of Orleans had been assassinated, demanded justice and redress; she subsequently withdrew to Blois, where in 1408 she died of unrelieved sorrow. Her tomb in the Cordeliers church displays her ultimate motto: « Nothing now means anything to me ». This large oil painting illustrates the theme of faithfulness beyond death. In the 19th century, romantic heroines, exalted sentiments, and sumptuous bygone centuries were highly appreciated, and « troubadour » painting was particularly valued.

It was to no avail that Valentine Visconti, whose husband Louis of Orleans had been assassinated, demanded justice and redress; she subsequently withdrew to Blois, where in 1408 she died of unrelieved sorrow. Her tomb in the Cordeliers church displays her ultimate motto: « Nothing now means anything to me ». This large oil painting illustrates the theme of faithfulness beyond death. In the 19th century, romantic heroines, exalted sentiments, and sumptuous bygone centuries were highly appreciated, and « troubadour » painting was particularly valued.

Oil on canvas (Inv. : 2008.7.1), ceded by the state to the town of Blois. This painting is displayed in Room 3 of the Fine Arts Museum.

The assassination of the Duke of Guise by Paul Delaroche and his workshop (1834)

Commissioned by Ferdinand of Orléans, son of King Louis Philippe, this scene represents the assassination of the Duke of Guise by order of King Henri III in the Chateau of Blois in 1588. The staging of the scene is highly theatrical, as the king appears from behind a curtain, greeted by his men in arms, and discovers the body of his enemy, lying motionless on the ground. In this romanticized decorative and historical fresco, we rediscover the 19th-century predilection for dramatic action.

Commissioned by Ferdinand of Orléans, son of King Louis Philippe, this scene represents the assassination of the Duke of Guise by order of King Henri III in the Chateau of Blois in 1588. The staging of the scene is highly theatrical, as the king appears from behind a curtain, greeted by his men in arms, and discovers the body of his enemy, lying motionless on the ground. In this romanticized decorative and historical fresco, we rediscover the 19th-century predilection for dramatic action.

Oil on canvas (Inv. 895.3.2, acquisition by the town of Blois).This painting is displayed in the Guises Room, in the François 1 wing.

Carved ivory horn (c. 1490-1930)

This object is an olifant, a hunter's horn made of elephant ivory. As a typical creation of the Sapi people (Sierra Leone), it was tailored to the demand of Europeans, who showed fondness for this type of 16th-century exotic object. That is one reason why the olifant features a vignette of deer hunting. More generally, princes would place orders for items from faraway colonies so that they could be exhibited for visitors in their cabinets of curiosities.

This object is an olifant, a hunter's horn made of elephant ivory. As a typical creation of the Sapi people (Sierra Leone), it was tailored to the demand of Europeans, who showed fondness for this type of 16th-century exotic object. That is one reason why the olifant features a vignette of deer hunting. More generally, princes would place orders for items from faraway colonies so that they could be exhibited for visitors in their cabinets of curiosities.

(Inv. 861.206.2) Donation from Monsieur de Martonne, app. 1860. This object is displayed in the Studiolo, in the François 1 wing.

Plate in Italian majolica (blue ceramic), by Francesco Durantino (1544)

This plate recalls the history of the nymph named Io, daughter of the Inachos river seduced by Jupiter. In his Metamorphoses, Ovid recounts how an infuriated Juno forced Jupiter to transform Io into a heifer and to offer her the « animal », before entrusting « it » to Argus the shepherd.

This plate recalls the history of the nymph named Io, daughter of the Inachos river seduced by Jupiter. In his Metamorphoses, Ovid recounts how an infuriated Juno forced Jupiter to transform Io into a heifer and to offer her the « animal », before entrusting « it » to Argus the shepherd.

Produced in Italy and highly appreciated by the Renaissance princes, this type of earthenware dish was not meant for practical use. Luxury items par excellence, Italian majolicas were presented on cupboards and credenzas and in collectors' cabinets as works of art.

(Inv. 2000.5.1, acquisition by the town of Blois). This work is displayed in the Studiolo, in the François 1 wing.

Miniature timepiece, by Barthelemy Cuper (c. 1620)

In the late 16th century, watchmaking was thriving in Blois. Tried and true watchmaker dynasties settled in Blois, particularly the Cuper family, established in the town from 1555 through the end of the 19th century. The extreme miniaturizing of this watch attests to the mastery achieved in the 17th century by the artisans of Blois, among whom Barthelemy Cuper, watchmaker of Marie de Medicis, queen of France, was a prime example.

In the late 16th century, watchmaking was thriving in Blois. Tried and true watchmaker dynasties settled in Blois, particularly the Cuper family, established in the town from 1555 through the end of the 19th century. The extreme miniaturizing of this watch attests to the mastery achieved in the 17th century by the artisans of Blois, among whom Barthelemy Cuper, watchmaker of Marie de Medicis, queen of France, was a prime example.

Gilded bronze (Inv. 86.11.1, acquisition by the town of Blois). This object is displayed in the New Study, in the François 1 wing.

Sambin cabinet (second half of the 19th century)

This imposing piece of furniture is a 19th-century replica of a late Renaissance cabinet conserved in Besançon. Its sheer dimensions attest to the monumentality and decorative abundance of late 16th-century furniture. The cabinet presents an ornately distinguished architectural decor, replete with friezes, foliation, festoons and eight panels representing mythological figures. It also attests to an interest in Renaissance art at the end of the 19th century.

This imposing piece of furniture is a 19th-century replica of a late Renaissance cabinet conserved in Besançon. Its sheer dimensions attest to the monumentality and decorative abundance of late 16th-century furniture. The cabinet presents an ornately distinguished architectural decor, replete with friezes, foliation, festoons and eight panels representing mythological figures. It also attests to an interest in Renaissance art at the end of the 19th century.

Woodwork, oak (2009.1.1, acquired by the town of Blois). This piece of furniture is displayed in the King’s Chamber, in the François 1st wing.

The martyrdom of Thomas More, by Antoine Caron (c. 1590)

Thomas More was the Grand Chancellor of Henri VIII of England. Having remained faithful to the pope at a time when Henri VIII was seceding from the Catholic church to form the Anglican church, Thomas More was decapitated in 1535. In Antoine Caron's representation, he is successively brought to the prison in the Tower of London and seen kneeling on the scaffold; after that, his head is exhibited on a stake in the background. This episode in English history clearly reflects the Wars of Religion destabilizing France: Thomas More had been transformed into a martyr of Catholicism facing to the rise of Anglicanism, which was conflated and equated with the Protestant Reformation.

Thomas More was the Grand Chancellor of Henri VIII of England. Having remained faithful to the pope at a time when Henri VIII was seceding from the Catholic church to form the Anglican church, Thomas More was decapitated in 1535. In Antoine Caron's representation, he is successively brought to the prison in the Tower of London and seen kneeling on the scaffold; after that, his head is exhibited on a stake in the background. This episode in English history clearly reflects the Wars of Religion destabilizing France: Thomas More had been transformed into a martyr of Catholicism facing to the rise of Anglicanism, which was conflated and equated with the Protestant Reformation.

Oil on wood (Inv. 29.5.9, acquisition by the town of Blois). This painting is displayed in the Wars of Religion Room,in the François 1st wing.

Virgin with Infant, anonymous sculpture (early 16th century)

This particularly beautiful sculpture is a rare example of production in the Val de Loire in the early 16th century. Inspired by the Italian example of the early Renaissance, the Virgin who holds her son in her arms expresses a novel notion of mother-and-child intimacy. The gracious swaying of the hips, the lovingly gentle gestures, the tender gaze and other subtle details render the sculpture animated and moving.

This particularly beautiful sculpture is a rare example of production in the Val de Loire in the early 16th century. Inspired by the Italian example of the early Renaissance, the Virgin who holds her son in her arms expresses a novel notion of mother-and-child intimacy. The gracious swaying of the hips, the lovingly gentle gestures, the tender gaze and other subtle details render the sculpture animated and moving.

Terra cotta (Inv. 869.35.1). This sculpture is displayed in Room 1 of the Fine Arts Museum.

A bust of Le Carpentier, by Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (1709-1778)

This portrait of Le Carpentier, who was an architect, member of the Académie Royale and friend of Lemoyne, reveals masterful virtuosity in the rendering of the flesh and the vivacity of the gaze. By the 18th century, the art of the portrait had grown more intimate, more intent on rendering a person's expression and character. As for the prestige attached to social status, which may be seen in the lace jabot and the French wig, it is all but eclipsed by the model's intelligent and dignified expression.

This portrait of Le Carpentier, who was an architect, member of the Académie Royale and friend of Lemoyne, reveals masterful virtuosity in the rendering of the flesh and the vivacity of the gaze. By the 18th century, the art of the portrait had grown more intimate, more intent on rendering a person's expression and character. As for the prestige attached to social status, which may be seen in the lace jabot and the French wig, it is all but eclipsed by the model's intelligent and dignified expression.

Terra cotta (Inv. 861.176.2). This portrait is displayed in Room 5 of the Fine Arts Museum.

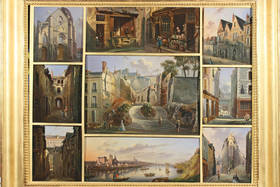

Views of Blois, by Eugene Gervais (1865)

The painter Eugene Gervais was a noted figure in 19th-century Blois; he was one of the first curators of the fine arts museum. In this original painting, the artist casts a glance not only on the large-scale transformations contributing to the modernization of Blois, but also on the picturesque streets of the old town. So it is that construction of the monumental Denis Papin staircase is environed by views of ancient abodes and byways.

The painter Eugene Gervais was a noted figure in 19th-century Blois; he was one of the first curators of the fine arts museum. In this original painting, the artist casts a glance not only on the large-scale transformations contributing to the modernization of Blois, but also on the picturesque streets of the old town. So it is that construction of the monumental Denis Papin staircase is environed by views of ancient abodes and byways.

Oil on canvas (Inv. 33.7.2 don Jolain). This painting is displayed in Room 7 of the Fine Arts Museum.

Large covered earthenware vase from Blois, by Ulysse Besnard (1881)

In the 19th century, Blois was a major center of ceramics manufacture. This covered urn was strategically positioned at the entrance of a workshop in order to attract customers; that is why it is so spectacularly large. It is also a genuine technical achievement that underscores the skills of the ceramicists. The decor of highly colored foliated scrolls typifies their art, in which they drew inspiration from Renaissance motifs, particularly those characterizing the Chateau of Blois.

In the 19th century, Blois was a major center of ceramics manufacture. This covered urn was strategically positioned at the entrance of a workshop in order to attract customers; that is why it is so spectacularly large. It is also a genuine technical achievement that underscores the skills of the ceramicists. The decor of highly colored foliated scrolls typifies their art, in which they drew inspiration from Renaissance motifs, particularly those characterizing the Chateau of Blois.

(Inv. 73.10.1, acquisition by the town of Blois). This work is displayed in the Neo‐Renaissance Room, in the François 1 wing.

Royal court ball, anonymous painter (late 16th century)

The ball was an important and popular entertainment in the Valois court. At once a place to meet and a site of prestige, it provided an occasion for a display of splendor in a colorful and lyrical ambience. This painting illustrates the introduction, during an elegant evening, of new dance from Italy, the volta. As the tiptoeing male dancer initiates a spinning movement, he lifts his partner and holds her up with his hands.

The ball was an important and popular entertainment in the Valois court. At once a place to meet and a site of prestige, it provided an occasion for a display of splendor in a colorful and lyrical ambience. This painting illustrates the introduction, during an elegant evening, of new dance from Italy, the volta. As the tiptoeing male dancer initiates a spinning movement, he lifts his partner and holds her up with his hands.

Oil on canvas (Inv. 872.3.2, Bequest of Louis de Grimoult, count of Villemotte). This painting is displayed in the Queen’s Gallery, in the François 1 wing.

Currently open from 10am to 5pm (last entrance at 4:30pm)